Lawrence of Aquilegia and the ars dictaminis

Or, how to address the Pope in 27 different ways.

While I have already covered the general notion of medieval use of graphs (i.e., nodes and edges) in a previous post, this particular post is about a specific form of graph-based reasoning within the ars dictaminis, or art of letter-writing1.

In the centuries following the decline of the western Roman empire, officials continued to communicate through written letters, though not at the level of eloquence of predecessors like Augustine and Cicero. The practice of writing letters starting around the 5th century was instead likely based on formulae, or model letters. A given formula represented a standard template for some scenario that its users may find useful, such as a contractual agreement, with placeholders for names and other variable pieces of information. Several collections of formulae are known to exist, providing their users with a means for writing letters based on a known set of situations. This approach to writing limited authors to only the set of scenarios the collections could cover, however, and in societies of growing complexity the static formulae could not hope to keep up with the demands of the time. In response to this need, scholars in Italy began to develop a more refined theory of written communication in the 11th century; it is here where the ars dictaminis, or art of letter-writing, began to emerge.

Initial developments in the ars dictaminis took the form of treatises on writing similar to those on rhetoric, with particular emphasis on the written rather than the spoken word. Like a speech in rhetoric, a proper letter had five or so parts, each of which had its own particular role in the letter. Of these, the ars dictaminis placed special emphasis on the introductory elements of the letter, with treatises providing long lists of proper terms of address depending on circumstance alongside stylistic recommendations.

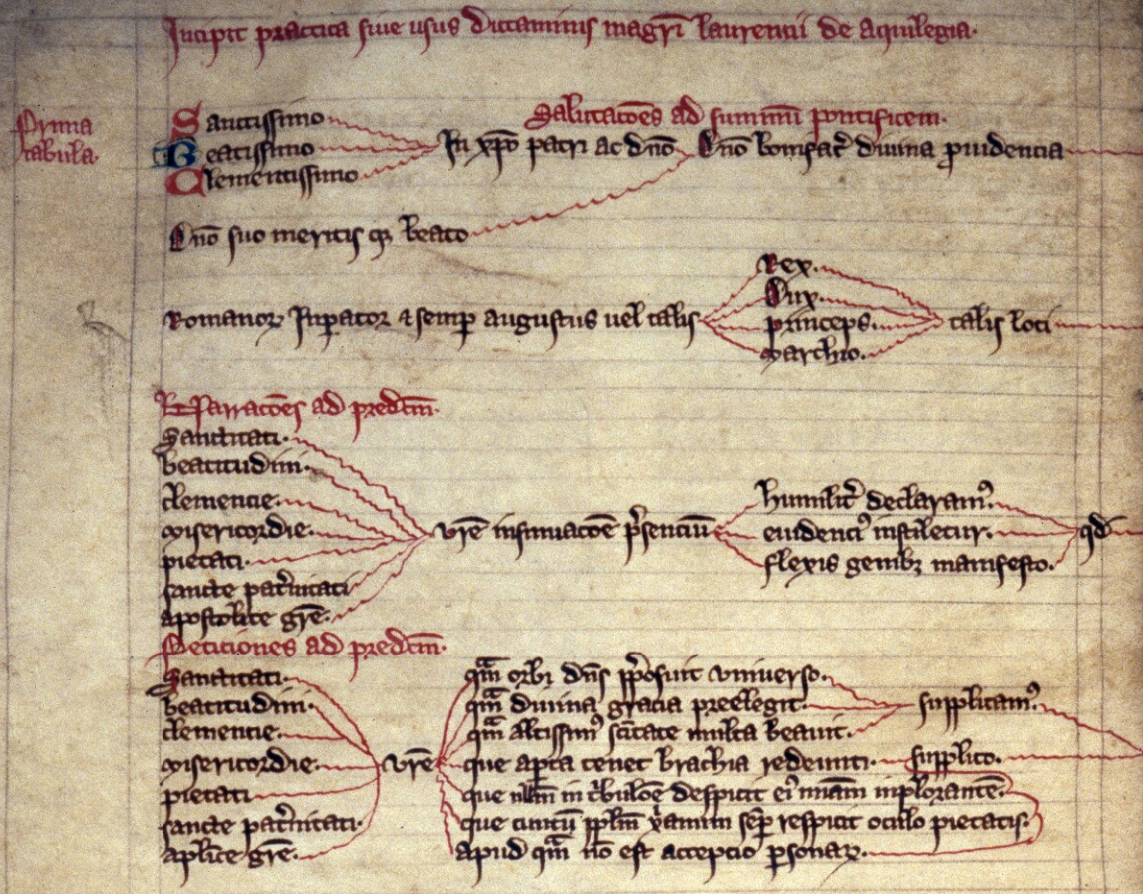

This began to change around the end of the 13th century. Around this time, or in the early 14th century, Lawrence of Aquilegia released his Practica sive usus dictaminis. Lawrence took a radically different approach to the ars dictaminis compared to his predecessors. Rather than provide descripts of letters and precepts for writing, the Practica contained a series of tables (or flowcharts) for a dictatore to follow in order to write a letter. Each step in the process contained a word or phrase, such as an introductory greeting or a term of address. Following the chart from one end to the other would produce a complete section of a letter.

Lawrence's intentions with this model are clear, with his writings claiming that any person able to write individual characters could compose letters using his method. This was, as Ayelet Even-Ezra notes, a slight exaggeration: a user of the Practica still needed to know Latin, and its many tables were still finite in the letters they could express2. Authors copying the Practica could, and frequently did, amend its tables as well to suit their own needs as a result. This practice ultimately found a wide audience across Europe, surviving well into the 15th century, following which oral discourse began to supplant written documents as a means of communication3.

Murphy argues that Lawrence's automated process for writing letters in the Practica represents a "rhetorical dead end" for ars dictaminis4, where all further development was mere replication of prior ideas. This is an understatement of what the Practica represents, both as a work in itself and an example of broader intellectual developments in the medieval era. Prior to Lawrence, nearly all treatises pertaining to rhetoric and ars dictaminis merely defined what is correct by way of various precepts and examples. Lawrence's major innovation was in recognizing that taken together, these precepts can be transformed from a descriptive doctrine into a generative process. What looks at first like an attempt to turn an art into mindless mechanics in fact represents something very different: a new understanding of the combinatoric nature of the ars dictaminis itself as a purely logical system of symbols and rules. Its major claim is that provided one knows the rules of the system, it is possible to generate valid statements without knowing anything else; the rules themselves are enough. The fact that Lawrence's system of choice was letters to the pope is of little importance.

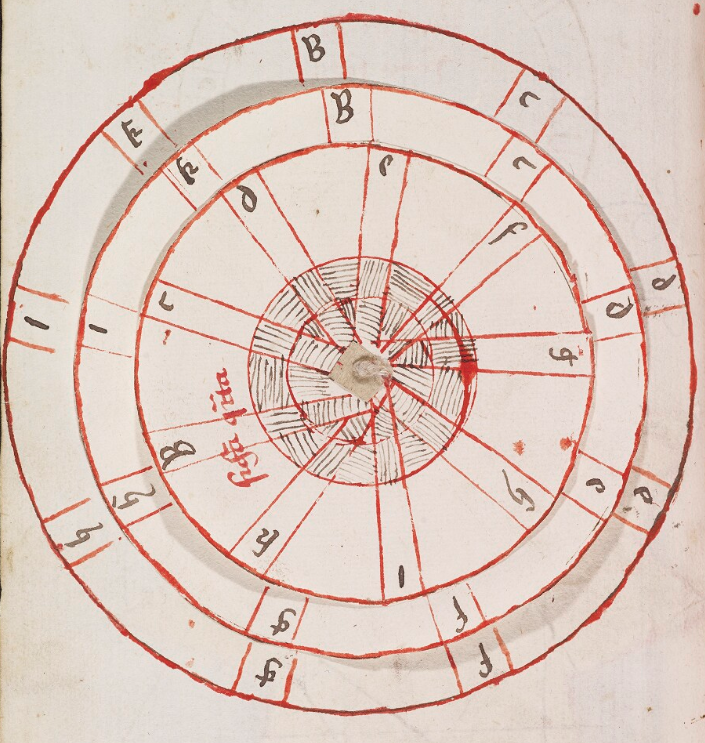

Such an approach has other advantages beyond providing a clear means of writing letters. Unlike the formulae of the early medieval period, a copy of the Practica could represent hundreds of letters in only a few short pages. Addition of a single node in a table of salutations could make room for hundreds more. While this form of combinatoric reasoning was a radical change for the ars dictaminis, it closely tracks with output from the era in other domains like Ramon Llull's Ars generalis, a means of logically deriving properties of God and reality via similar systems of symbols and rules5. It may be significant that at least one copy of the Ars is located in the same manuscript as a copy of the Practica.

Naturally, there are limits to this approach to writing. A formal system for generating statements can only ultimately generate statements valid within that system, and the fact that those statements are valid as a group of symbols does not mean they make sense as a statement about the world. In this sense, Murphy is correct in his assessment that such rigid automata cannot express all ideas; some things will always lie outside of the boundaries of the machine.

This does not mean Lawrence's ideas were without merit. The Practica itself was clearly of use to medieval scholars for centuries following its initial publication. Far from being a futile effort to build systems of thought in ways that we now know to be impossible, or a medieval curiosity that has left only faint traces on the modern world, the work of Lawrence and his contemporaries laid the foundation for a number of mathematical and technological developments. Its method of algorithmic writing reflects a method of text generation using what we would today call directed graphs, and modern computation as we know it draws heavily from the same notions of graph traversal Lawrence put forth in his works. Language design, for example, relies entirely on formal grammars and automata that look strikingly similar to the tables of the Practica. The semi-official website6 showing the grammar for JSON, a popular data format for web applications, is a particularly powerful illustration of this.

As Murphy notes, the ars dictaminis arose in response to a need7. When a problem emerges, solutions can come from unlikely places, and those solutions themselves may take on a life of their own. Perhaps it is more correct to say that Lawrence's work was not the end stage of the practice of letter-writing, but the beginning of a union of language and logic whose effects are still playing out today.

- James Murphy's Rhetoric in the Middle Ages provides an excellent overview of the development of rhetoric and the ars dictaminis in the medieval era. Unless cited explicitly, much of the background material for this post comes from this work.

- Even-Ezra, A. Lines of Thought. p134

- Even-Ezra, A. Lines of Thought. p219

- Murphy, J. Rhetoric in the Middle Ages. p261

- https://quisestlullus.narpan.net/en/art

- https://www.json.org/

- Murphy, J. Rhetoric in the Middle Ages. p267